Meet Roshni Nuggehalli and Marina Joseph of YUVA

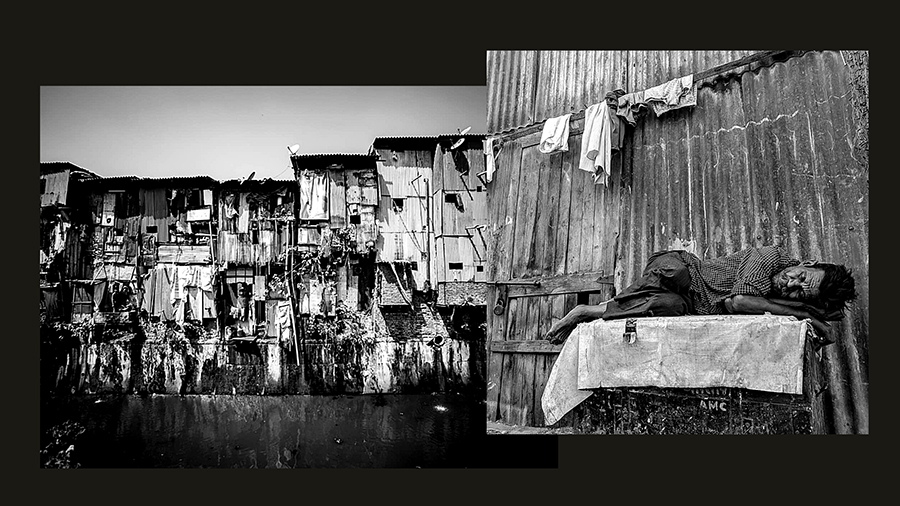

by Anupama Mandloi July 19 2020, 10:38 pm Estimated Reading Time: 15 mins, 48 secsIn this time of Covid-19, the world has witnessed upheaval in almost every sphere of life while impacting the social fabric of society. In India, we were forced to sit up and take notice of the marginalized sections of our society when innumerable citizens began to literally walk out of cities that couldn’t stand by them in their time of need. The stark divide between the rich and poor was underlined for all to see. While policies, infrastructure and administration failed to relieve their pain, several NGOs, countless individuals came together to help.

I had the good fortune of speaking with Roshni Nuggehalli, Executive Director, YUVA and Marina Joseph, Associate Director, YUVA on their NGOs evolution and its role during this time of crisis.

What prompted the creation of YUVA? And, what is the story behind the name?

Roshni: In the late 1970s, a group of students of Nirmala Niketan College of Social Work, Mumbai, ventured into the informal settlements of Jogeshwari as a part of their coursework mandate. Their work in the slum (bastis) inspired them to draw up a full-fledged program for youth; to develop a rights-based approach to address structural inequalities and respond to the issues of the most poor and marginalized. They believed that when the marginalized were made aware of these inequalities, they would come together to address them. Thus the program aimed to develop a young leadership among vulnerable populations who could own and lead change efforts.

A few years later, on 30 August 1984, Youth for Unity and Voluntary Action (YUVA) was formally registered as a voluntary development organization supporting and empowering the oppressed and marginalized by primarily concentrating on their human rights.

Initially YUVA’s work concentrated on channelizing the energies of the youth and encouraging them to participate in the development of their community. It could not have been a more apt time, as 1985 was declared International Youth Year by the United Nations to focus attention on issues of concern relating to the youth.

While working directly with young people concerns of women emerged, as did concerns of settlements they lived in like housing, forced evictions, water, sanitation etc. So gradually our work expanded to various geographies and concerns of the urban poor. Overall our work was based on commitment to ensuring human rights for all, and against discrimination.

YUVA still has a strong youth focus and a young team as well. But our mandate in terms of work has expanded into multiple areas since. The name stays.

What has changed in these 35 years - be it people who donate or the issues you stand for?

Marina: With regard to issues we stand for – the core focus on human rights of the poor and most marginalized remains the same and our method of engagement as well. But in terms of the situation of those we stand with and their issues, so much has changed, yet so much has stayed the same. We were dealing with bastis being forcibly evicted in the 80s and we are doing this even today. There was a lack of access to rations then, even as the COVID-19 induced lockdown continues – lack of access to ration remains a huge focus of our work.

Our country has changed, developed, our cities are now ‘smart cities’ with WiFi and CCTVs etc. but the societal structures (caste, religion, gender) that keep the poor, poor and the oppressed, oppressed have not changed. We still have people from the same caste cleaning our streets and gutters. Their parents were doing it in the 1980s; their children are doing it now. The same with domestic workers and other such work. There are of course exceptions. But look at the norm.

Roshni: With regards to those who donate – much has changed for NGOs. Earlier NGOs were given what is called “institutional funding” - a donor trusted and understood the organization, and committed to a long-term flexible partnership. Donors understood that social change is not a 1-3 year project, which can be neatly implemented, delivered, with a bow on top.

They understood this is a complex activity.

The agenda was decided mutually and based on a bottom-up method. Now however, the focus is only on 1-2 projects with ‘quick-fix’ solutions. There is tremendous pressure to show results, even if they are superficial. Donors also always ask - what is your planning for ‘scaling-up’ not realizing that cookie cutter approaches fail miserably. CSR is especially guilty of this.

There is also a sense of we-know-better-than-you because we do business. There is a long way to go before money that comes in will actually benefit those who need it, in a deep and sustainable way, and uphold dignity and respect for all parties involved. There are new laws; rules and donor organizations have changed the way they donate.

The number of Indian philanthropists has increased but philanthropy isn’t the extent to which one sees in the west. High net worth individuals too face many challenges - diligence is what most time goes towards - either personally or through ‘conduit’ organizations. Fair enough because there are a lot of problematic NGOs too, but if the focus was on building relationships, trust and understanding the issues, we feel the impact of their money will go much further. CSR has begun, but it has a long way to go before it matures and grows as a support to civil society in India.

We live in surreal times. What is it about these times that really stand out for you?

Marina and Roshni: People’s generosity, willingness to give at a time when it is needed. Willingness of our teams to put themselves at risk, go beyond all formal ‘JDs’ ‘KRAs’ and do such phenomenal relief work, because of the real commitment to the work we do.

The resolve of ‘civil society’ and the genuine collaborations – organizations, groups of students, communities, individuals to move beyond boundaries – that have done so much at this time to ensure people do not starve, can travel home with dignity. Compared to every other sector, civil society’s clear sense of purpose is what has been able to ensure some relief and dignity. This has to be recognized and clearly appreciated, not through rhetoric but through creating supportive environments for civil society to function in a vibrant way in the days to come.

Absolute apathy from the state, still engaged in propaganda and a divisive agenda even in these times.

What do you think could have been tackled differently by you or by the other support structures with reference to migrant labor?

Marina: The WHO declared the Corona as pandemic on 11 March 2020, on 22 March the Janta curfew took place (announced on 19 March) and only on 24th March midnight did the lock down begin (announced 4 hours prior). That’s a lot of time for the lockdown to have been thought through. If trains were kept operational for a week after the 19th with strict instructions that movements would be prohibited after, a lot would have been different.

Government departments could have collaborated with civil society organizations to develop a relief mechanism early on.

How did you arrive at your strategy of dry rations and then cooked food and monthly kits and how do you think this made a difference?

Roshni: We have our ear to the ground. So we knew we had to do this early on. Beginning around 15th March we began hearing from people living in bastis that they were not able to get work. From 17th to 19th March we conducted a rapid needs-assessment in 4 cities in the Mumbai Metropolitan Region to understand the impact that the gradual closing of work places meant for the urban poor. The findings were alarming with regard to access to food and work.

This informed the need to begin relief work through dry rations to needy families. When we began our fund raising campaign on 18 March, we didn’t know how many people would support this work.

As an organization we have money allocated in projects for project specific work – relief was not something we had funding for. We would later end up speaking with existing donors for their support but we would definitely need individual donations at that point.

With the money that came in we began distributing weeklong ration supplies. This continued till the end of March. By then the lockdown was formally announced and we realized this would mean even more deprivation faced by those dependent on daily wages. Hence we decided to start providing ration kits with monthly ration supplies.

What were the reactions to the help received by the vulnerable and in need?

Marina: Reactions have been mixed. Some people are very grateful, some don’t say anything – one needs to realize that no one wants to beg or take something for free. These are people who have been working and earning a living. People essentially want to earn. That’s where their dignity is.

You were addressing largely the migrant population. Where did you position your teams to be of maximum impact; since they were constantly on the move?

Marina: I would make a correction here. We were reaching out to vulnerable households living in slums (we use the term bastis), the homeless; those living in gaothans - resettlement colonies – some are migrants some are not. Depends on how the word ‘migrant’ is defined – based on the number of years in the city? Socio-economic class?

Roshni: We had four major hubs of work - one in Navi Mumbai-Panvel, one in Eastern suburbs-Island City, one in Western Suburbs and one in Vasai-Virar. Each team had 3-4 members, all-living in and around the areas of distribution. That way we ensured that least amount of travel far away from home. Our stocks were stored at our center in Kharghar and transported to these different hubs as per the need. This was efficient, kept our work locally rooted and also impactful.

Marina: For the migrant workers who decided to travel home, our support was as follows - our teams chose spots where travelers had to pass – nearer tolls, highways, state transport bus stands – they relied heavily on local knowledge of routes out of the city.

For the ration distribution - we first distributed in areas where we have existing work, then followed by other areas where needs were brought to our notice. We did this through partnering with local Community Based Organizations (CBOs), NGOs, etc.

Can you share some situations that you think you will always remember from this time?

Marina: We run a labor helpline as part of our ongoing work where we deal with issues faced by construction workers. However, when we had shared posters to fundraise with the phone numbers of our colleagues, within days they received almost a hundred calls daily from stranded migrant workers who were in desperate situations without any ration. We later heard that the Jharkhand government had publicized these phone numbers as where to get support from in Mumbai. We were able to provide relief to many such requests.

Roshni: Media support – Many journalists covered stories of people in distress, this helped us identify areas where there was a need for relief.

In Vasai, for example, we were appalled at the level of lack of information, people panicking, no one to support them, sitting with families fur 3-4 days in the hot sun, waiting, hoping for a call to board a train, then having to leave disappointed, find a place on the street to live since they have given up their rental homes. The level of uncertainty, precariousness and invisibility as well as rejection the people who contribute to the city have felt - this stark reality will never leave us.

As an organization we always knew that the people who are essential in a city are never valuable. The lockdown brought this out into plain view for everyone to see.

Can you elaborate on this last line in your previous response, ‘As an organization we always knew that the people who are essential in a city are never valuable?’

Marina: Most Indian cities are exclusionary in nature especially with regard to those who lack any form of capital - largely called the poor. Their homes and places of work are constantly evicted; they are called 'encroachers' or 'non-tax payers’. Their locales lack the most basic things - water, toilets, schools, and health care facilities. But such few people raise a voice about this. So in a sense, the migrant crisis just made it so visible for everyone to see that as a society, we have such little care about the everyday lives of those who keep our homes, the city and the economy running - our domestic workers, gardeners, liftmen, security, vegetable vendors, street food vendors, auto drivers. The list is endless.

Where did you find support?

Roshni: Multiple people who contributed large and small amounts, existing donors from India and abroad, large Indian philanthropies that have really been such a huge support during this time.

We have a young team and fully focus on their own independent leadership – this is a huge organizational support. Since in a time of crisis, we have people taking ownership and making things happen.

Our community engagement model is collective led. So we did everything with the clear focus of most marginalized and full partnership with local groups, youth groups, CBOs – they are a huge support during relief to ensure those in need have kits delivered to them.

Were there any areas where you could have done with more help and support?

Marina: A lot of people came our way quite serendipitously, if we can say so. I think we received a lot of support in so many ways. You and Tanuja included!

A huge learning has actually been working with those who normally don't speak our language.

What do you mean by that?

Marina: YUVA has always been know to be a rights based organization, and we don’t get the kind of buy in on the issues we work in - forced evictions, wage thefts of informal workers, building collectives of people, rights-education - but through the pandemic, many people who would otherwise not be convinced about these issues were willing to support the work we were doing.

Did the government provide any sort of assistance to help you achieve your desired goals?

Roshni: We received permissions to travel from the police and civil defense. The police partnered us on several relief efforts. Bureaucrats were largely aware of relief work going on and were supportive.

The Municipal Corporations, District Collectors - they have reached out to us to assist them.

People have a short memory. Now that the migrant labor has found its way back home, do you think the issue is resolved? What problems do you anticipate and what do you think needs to be done?

Marina: For India, the impact of this lockdown will be felt for the next few months, possibly even years. The impact on the poor is multifold. It has impacted children differently, women differently, migrant workers differently.

Migrant workers come to cities to work because of a lack of employment opportunities in rural areas and they use this money to support their families in the village. The government has said they will increase the daily MNREGA payment in rural areas. But this will not solve the complete problem of lack of work. There is also a fear about returning to these cities, given the way they were forced to leave.

People have exhausted all their savings - this has an impact on restarting work for those who are self employed. This will also have an impact on decisions to invest on education, pulling children out of school to support the family, etc.

For a city like Mumbai this is a problem too when the formal industries are all so dependent on this invisible workforce. Policy think tanks have started talking about an urban employment guarantee scheme to combat the loss of employment due to the dip in the economy. People need work; work provides people with a sense of dignity and freedom. Relief is not a solution to the situation in the long run.

What work are you now focusing on?

Roshni: We aim to complete providing relief during the monsoons. Simultaneously, we are ensuring that people access government relief schemes, welfare and social security entitlements, our Childline (children’s emergency helpline) team is responding to cases of various forms of violence among children. We have a 360-degree approach of working in communities - we work with children, young people and with adults – and we are finding new ways of working with these groups. We are also looking at supporting people as they rebuild livelihoods in the city or re start work.

Most people want to contribute but are not sure whether their money is being put to the right use? What would you say to them and what tips would you give them to help identify the charity of choice.

Marina: Trust. Find an organization you trust and support them. NGOs aren’t resource rich, we don’t make profits, and there are strict rules that govern the use of funds that come – and audits too. There is minimal scope for it to be misused.

As much as someone donating wants the 1000 rupees they donate to go into purchasing a food kit only – one needs to understand the supply chain that goes into ensuring the person in need gets that food kit dropped to their doorstep. One needs people to be paid to do this, transport to be paid for, packers to be paid for, PPE needs to be available to those doing front line work etc. So while donating is important, it is also important to acknowledge one’s donation to an ecosystem that is trying to ensure the poorest can live with respect and dignity. One must acknowledge that any donation towards collective action, signing petitions for example, will ensure that those in power are held accountable.

I would ask you two things: Do I want to do something about this situation? Do I trust the organization?

If the answer is yes, go ahead and donate – it goes a long way!

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)