-853X543.jpg)

Mise en scene: a metaphysical expression

by Sharad Raj May 26 2021, 12:00 am Estimated Reading Time: 8 mins, 27 secsSharad Raj writes that to arrive at one’s mise en scene is to liberate oneself from dogmas that are both personal and intellectual.

The dictionary definition of mise en scene is as follows: The arrangement of the scenery, props, etc. on the stage of a theatrical production or on the set of a film. The setting or surroundings of an event. Robert Bresson in his now famous press conference of his last film, L’ Argent (Money, 1983) vehemently rejects the use of the term mise en scene in cinema for it is taken from theatre and by now film buffs all over the world know that Bresson tirelessly pursued his art in shaping cinema as an independent art form, the art of cinematography, as opposed to staging and performance.

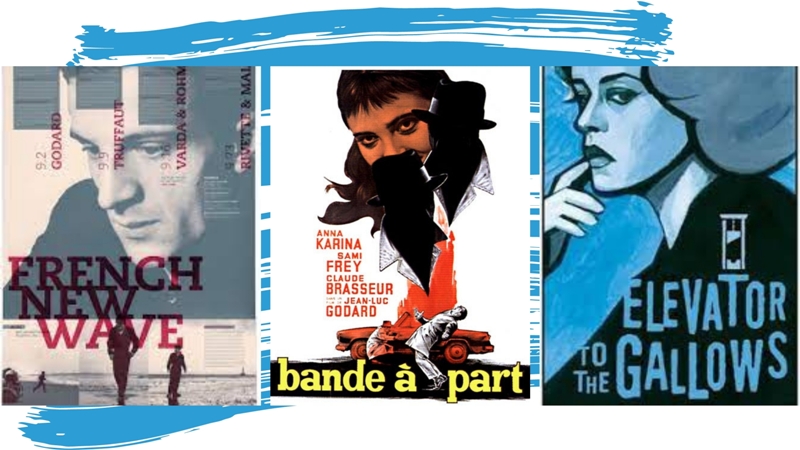

Having said that, the concept of mise en scene formed the very foundation of the Cahiers du Cinema group and the French New Wave. For the French Nouvelle Vague it was the unique and personal mise en scene as explored by a filmmaker that made him or her an auteur. The New Wave bandwagon, comprising Jean-Luc Godard, Francoise Truffaut, Agnes Varda, Claude Chabrol, Jacques Rivette, Eric Rohmer to name a few, contested that a film like a painting or literature needs to carry the signature of the maker. A work of Picasso or Matisse can be distinguished for their distinct aesthetics and style despite being in the modernist tradition.

The plays of George Bernard Shaw and Henrik Ibsen are both unique to their respective creators; or the same Raga Yaman is transformed by the interpretation of two different Hindustani Classical vocalists. Yaman of Bhimsain Joshi marks the stamp of its evolution in the Kirana Gharana, while Mallikarjun Mansur lends to the same Yaman the nuances of the Jaipur-Atrauli tradition. The New wave masters strived, advocated and struggled for the same autonomy of authorship for a filmmaker and realised that it is the distinct mise en scene as employed by a director that gives the film its unique identity.

1.jpg)

For the uninitiated, mise en scene of a film comprises every element and the manner it has been used by a director in the pursuit of his personal voice. From narrative structure to the use of time and space, elements of cinematography, colour, production design, sound design, pace and rhythm, music, dialogue, acting style et al are elements that contribute to the mise en scene of a film. And each of these elements can have a definite emotional, intellectual or dramatic purpose in a film.

Each auteur makes his choices of which among these he wants to use and how. It is what gives the film its form in a way. The manner a film artist may choose to sculpt time or dynamize space will vary from maker to maker. So will the elements listed above and their use depend on how different film directors employ them? If Godard accidently arrived at the jump cut then Varda and Truffaut showed signs of freedom of narrative structure and Rohmer made speech cinematic and stripped his visuals to bare minimum. Even Bresson, the self-proclaimed anti-mise en scene artist transfers his narrative onto the soundtrack and distils the visuals of his film of even a semblance of appeal and flamboyance in L’ Argent (Money).

Ironically, as a teacher and student of cinema both, it is the example of Bresson’s Mouchette (1967) that I often quote to underline the importance of mise en scene in cinematic unfolding of events, characters and situations. The basic storyline of Mouchette sans all thematic preoccupations of Bresson is very simple; it is the story of a teenage village girl, with an ailing mother, a drunkard father and a village goon stalking the young girl. But it is an all-time great film because what Bresson does cinematically, using his minimalistic, meditative modes of expression, is employ the mise en scene, which makes Mouchette a masterpiece of cinema.

1.jpg)

Likewise, the cinema of Yasujiro Ozu. The moment you propose a family drama the common proclamation is, “Oh it’s so tv!” So how does one account for perhaps the most unique mise en scene and temporal ellipses in films of Ozu or say a Shoplifters (2018) of Hirokazu Koreeda. The great auteurs converted the simplest, the most cliched or threadbare storylines or ideas, whatever one chooses to call them, into major works of cinema. Take Godard’s Breathless (1960) for example, the film where he arrived at the jump cut, cannot boast of much of a story but what it can boast of is exemplary form that amalgamates with various thematic preoccupation of the debutant director. For that matter Truffaut’s 400 Blows has loosely connected vignettes from the life of a young boy.

Andrei Tarkovsky in his list of filmmakers he deeply admired and looked up to names directors as varied as Robert Bresson, Akira Kurosawa, Ingmar Bergman, Kenji Mizoguchi, Luis Bunuel, Michelangelo Antonioni and Charlie Chaplin. Each of the masters of world cinema have a uniquely distinct style that comes from the choices of mise en scene made in their pursuit to be regarded as authorial voices of their films. If pursuit of truth can be considered one of the purposes of art then they seem to be seeking “truth”, Tarkovsky opines, albeit through different paths. None of them have anything in common with the cinema of Andrei Tarkovsky yet he calls them some of the greatest filmmakers to have graced the art of filmmaking. Same can be said about all the masters of the French New Wave. In fact there were major differences between Godard and Truffaut.

This brings us to the point that a maker’s formal choices and mise en scene is something that after a point cannot be taught from books or in film schools. They can only introduce us to the concepts of mise en scene, expose us to all the literature available. After that It is a personal journey, a journey of self-discovery of an artist, as and when he or she decides to seek truth, delve into deeper meanings of life and respond with sensitivity to the world around. It is a difficult journey, arduous and tormenting to emerge with aesthetics that truly represent the maker and his response, and understanding of life, to the world he inhabits. Trying to make sense or comprehend life going by while we remain busy in our tasks of creation is a complex and complicated state of mind to be in.

_(6)1.jpg)

Most struggle with it and those who come out of it are the ones who we call masters; of course in a relative sense, for the quest of an artist and the inner struggle associated with it is a lifetime process. Within their formal choices one finds Bresson evolving from Mouchette to L’ Argent, Ozu mature from Tokyo Story (1953) to Autumn Afternoon (1960) and Godard evolve from Breathless to Image Book (2018).

And this is why discovering and arriving at one’s mise en scene is a spiritual experience, for it can only and only be an inward journey, into the darkest and the brightest cockles of our inner being. And this has no end; it is infinite. Perhaps the only way an artist can express his world view or rather his response to life that is unfolding in front of him continuously.

Mise en scene is an artistic assembly of elements of cinema, in a manner the creator of the film thinks is best suited to represent his own self. It is oneself that we need to see in our mise en scene. Therefore there can be no hierarchy if this artistic endeavour as it is so deeply personal. How can one prioritise the static shots and multiple cuts in the films of Yasujiro Ozu and Robert Bresson over the languid long takes of Tarkovsky and Mizoguchi? How can we say that Rohmer and Woody Allen are verbose, for both have cinematised the spoken word. We may have our favourites and someone we may want to follow; we may also have a difference of opinion on the position one takes on a given art form, yet, they are all masters as they all have independent voices.

Pablo Picasso and Henri Matisse, Paul Gauguin and Van Gogh, Claude Monet and Paul Cezanne, Satyajit Ray and Ritwik Ghatak, Rabindranath Tagore and Premchand, are all artists as diverse as apples and oranges but they have documented the world around them with the flourish and intensity of an artist who digs deep. This internal process and its outcome both are metaphysical, therefore, in my view. There shouldn’t be any guidelines to this search and no predetermined rules can make this process of discovery subservient to their command. To arrive at one’s mise en scene is to liberate oneself from dogmas that are both personal and intellectual. If as filmmakers we remain enslaved to the book, then it may just stunt our growth as artists.

Command over craft is meant to help us in realizing our aesthetic aspirations, they are not the end in itself. Therefore different artists will express themselves differently. As a student of cinema I have always felt that there are as many mise en scenes as the number of auteurs an art form may have. There can be no fixed position on something as unknown and abstract as arriving at one’s artistic expression.

Of course in its short history, film art has arrived at certain positions that are considered aesthetically valid, therefore it does not mean that anything crass can pass off as art. There has to be synergy, either at peace or in conflict with the thematic preoccupation of the film and the formal quest of the film director. However, a more dogmatic approach to form can only kill an artist. And that will be a very sad day. This specially is the problem with Indian art cinema, but this is not the place to discuss that. May a million mise en scenes co-exist. As Bresson says, “ feel and express!”

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)