-853X543.jpg)

TOUCH OF JOY: JOY BIMAL ROY

by Aparajita Krishna April 28 2022, 12:00 am Estimated Reading Time: 29 mins, 15 secsI shall cherish the materializing of this article. The attempt is to visit the great cinema-maestro Bimal Roy through his son Joy Bimal Roy’s childhood memory and as an adult cine-goer and professional, writes Aparajita Krishna.

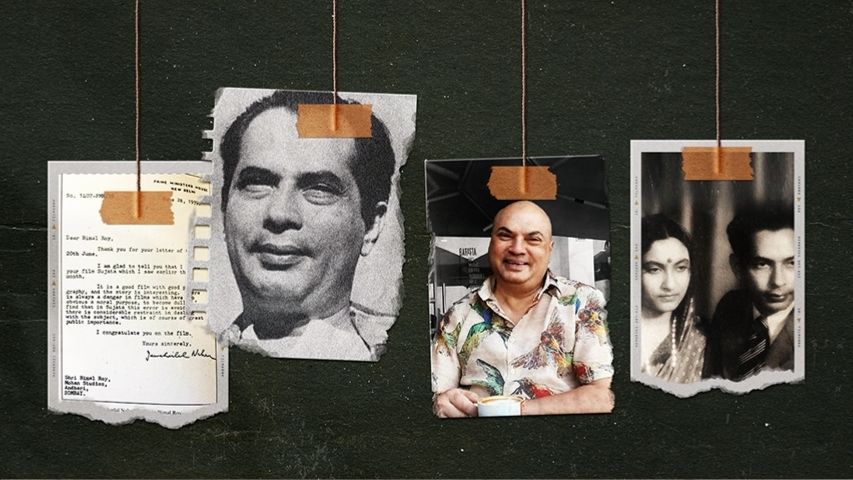

Joy lost his father when he was just 11. That absence would mark his growing-up years. Bimal Roy’s films would have been the presence via which the son would well have connected with the departed parent. What a legacy! Joy has preserved the heirloom with great care; a valuable collection of his father’s memorabilia. He shared the letter Jawaharlal Nehru personally wrote to Bimal Roy after watching Sujata. The letter dated June 28, 1959 is herein.

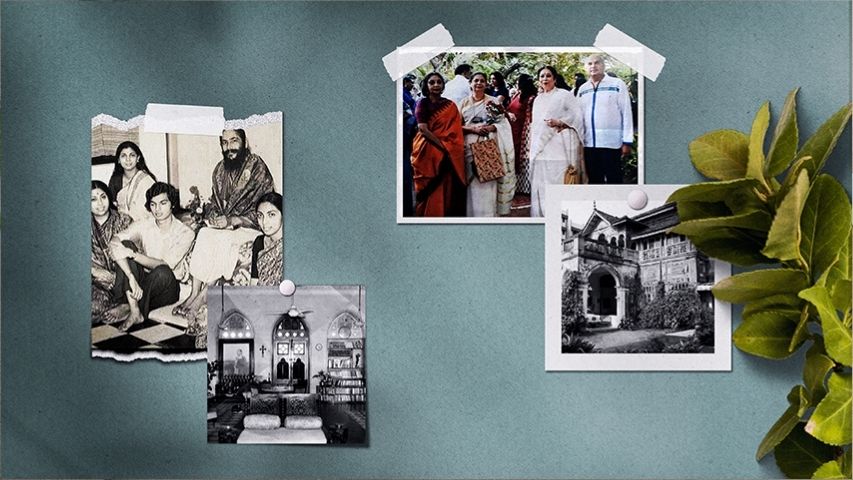

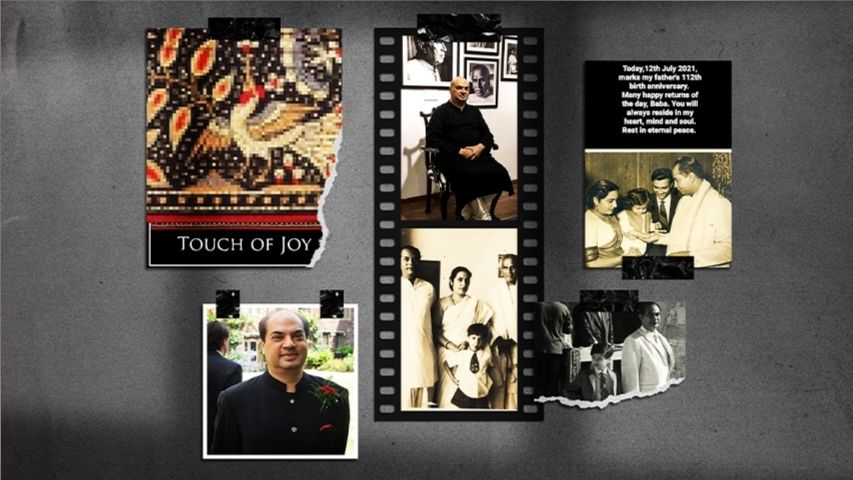

We get talking about Bimal Roy as a man and filmmaker. He was a humanist with a very calm and almost meditative passion for cinema and people. Son Joy also tells us of the family-man in the filmmaker; one who had a deep bond with wife Manobina Roy and their three daughters and son. This article is also about Joy’s own life, his philosophical-make and his work trajectory. As a designer his saree-clothesline is called Touch of Joy!

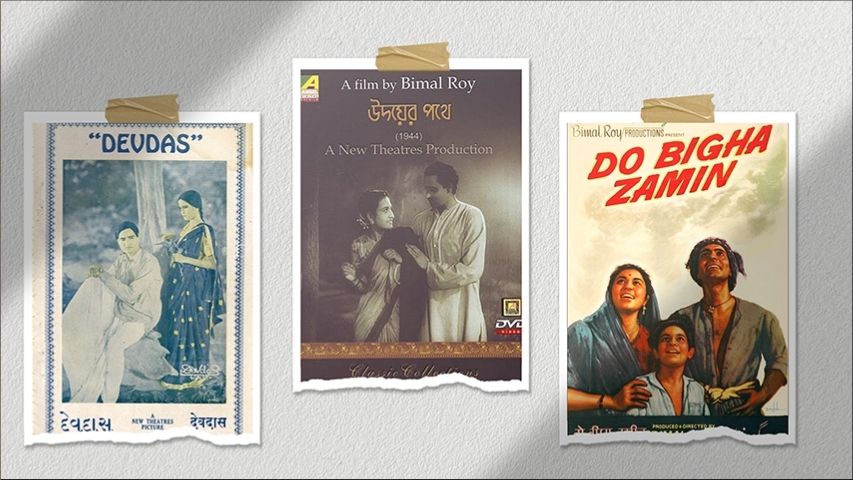

Joy, to address Bimal Roy’s repertoire as a director, writer, cinematographer and producer, befits books. The more you write about him the less it is. In this article I intend to visit your work profile and re-visit the great Bimal Roy through you, the son’s gaze, prodding your littlest memory and evoking your very fine cine-mind as an adult. To begin in the now. 56 years after his early death, Bimal Roy remains even more relevant. Parineeta, Devdas re-makes will come and go, but the 1953, 1955 one’s will remain immortal. Tell us how light or heavy does the great Bimal Roy legacy sit on you?

Although my father's legacy is the greatest privilege any son could ask for, I have to confess it has always weighed very heavily on me. Most people have this strange and unreasonable perception that filmmaking is a hereditary process. It took me a long time to overcome my guilt when they asked disapprovingly: ‘Why aren't you following in your father's footsteps?’ I am now 67 and I am finally at peace with myself. I am glad I didn't make movies. I would have never lived down the comparison. There can be only one Bimal Roy. I am proud to be his son and bask in his glory. I don't need any further badge of honour.

Your beautiful ancestral house on Mt Mary Road, Bandra, further defined the family. I recall visiting it. Your father got it built or bought it?

The house you remember visiting was Godiwala Bungalow, but it was demolished in 2002. It was indeed a beautiful home. It became like a shrine in my father's memory. All his personal possessions remained just the way he had left them. Sometimes I felt my mother expected him to return someday. He spent the last 12 years of his life here and they were arguably some of the most fulfilling years.

Most of his iconic films like Devdas, Madhumati, Yahudi, Sujata were made here. They brought him international fame and glory. The house became the subject of a case study for the students of J.J. College of Architecture. Subsequently it was nominated by the Indian Heritage Society as one of the best Heritage buildings in Bombay. Sadly a few corrupt individuals managed to get the house deleted from the list in order to facilitate the demolition. The rest, as they say, is history.

Saw your website Portraits In Faith. One also learns that you have a Guru. You are spiritually inclined. Do share the philosophy you live with.

I don't have a single philosophy. There are just a few principles I follow in life's journey, which I have picked up along the way from various sources. From my late Guru, Shri Mouni Baba of Ujjain, I got a very practical philosophy. He said: Chalte raho. Keep walking. Just keep going ahead regardless. He also emphasized the importance of laughter in one's life. I have taken both these principles very seriously and much to the discomfort of certain serious-minded people I find humour in even difficult times. More importantly I can laugh at myself.

From Reiki I picked up two more principles. The attitude of gratitude - I am grateful for everything I have and receive. Also, the reiki shrug - deflect criticism and rudeness by simply shrugging it off your shoulder and not let its toxicity seep into your system and corrode it. Easier said than done I suppose. And on my own I have come to a few conclusions: first, that one should live each day of one's life as though it is your last, second, live without regrets and third, never harm anyone consciously. I have also learnt that one can say anything to people provided it is said politely. So, my principles are all practical and not esoteric. It is important to live life simply and be true to oneself.

What is your work or leisure engagement in the present? You work at clothing, textiles and interior designs.

By God's grace, at present my work gives me a pleasure that happens only to a lucky few. I feel blessed that my work and leisure have merged together into a seamless whole. On 1st January 2020, my sister Yashodhara passed away. She was one of the most elegantly dressed women I have ever seen and she only dressed in sarees. Her collection was exquisite. Many relatives and friends had admired her sarees and had jokingly said that she should leave them her sarees. So, after her death we started distributing her sarees among our relatives and close friends. But I realized there were more takers than there were sarees. I wondered what to do. I then found several old borders that were torn. So, I began to create sarees out of these elements. I enjoyed the process so much that I wondered how to continue it even after Yashodhara's cupboard was empty. It was then that I hit upon the idea of sourcing old sarees from relatives and friends as donations. I would then upcycle them and sell the saree and donate a major part of the proceeds to Shanti Avedna Sadan, a hospice for terminally ill cancer and AIDS patients. I was fortunate that Radhi Parekh of Artisans unhesitatingly agreed to keep the sarees in her beautiful store in Kala Ghoda. The whole process from getting the sarees, buying fabric and borders, drawing out designs for the tailors to understand the design in order to upcycle them is a solo operation. I have designed over 200 sarees and continue to do this till today. I find the entire exercise therapeutic and creatively satisfying. It’s called Touch of Joy.

I am house proud so I like being surrounded by beauty and harmony. This takes up a sizeable portion of my leisure time too. My work has become my leisure and my leisure is my work and the combination gives me pure pleasure. Such a joyous discovery!

In addition, I was foisted with the job of bringing out a newsletter for a Trust I am part of. The Promenade is the quarterly newsletter of the Bandra Bandstand Residents Trust. It's tough both creating and collecting the inputs, but with the second issue I realized that I actually enjoyed the process and it has become a labour of love for me. The Newsletter is completely my baby. I have the freedom to write what I want. I have got a lot of appreciation for it. I don’t know if I have a way with words, but I follow my mother’s advice. She told me ‘It is difficult to be simple’. I strive for simplicity so that everyone can understand what I say.

Joy, the consummate writer, can also write with a kept in-check/cheek- humour. An edited excerpt in his newsletter dated April 2022 reads, ‘In this editorial I thought I would share my vivid memories of growing up in Bandra 60 years ago. Bandra was considered the boondocks by the SoBo crowd in my youth. I remember sometime in the early 1980s, a SoBo (South Bombay) lady visiting our home for the first time declared that she felt unwell whenever she crossed Worli.’ Another bit reads, ‘We lived on Mount Mary Road, lined up with handsome bunglows on either side. All the families knew each other so much that our neighbour across the road, Uncle Madhavdas Mody, would do his entire socialising by simply standing at his front gate every morning, exchanging pleasantries with all who passed by. In the evening he would reposition himself at the gate again and get an update on their work as they made their way back home.’

Another anecdotal passage reads, ‘There was one more attraction on Hill Road. Our somewhat worse for wear neighbourhood movie theatre New Talkies, with tattered red seats, whirring fans overhead, and friendly mice playing leap frog over our feet! But we loved the place, and the four anna packets of potato chips and the two-rupee choco-bar ice cream we devoured during the interval…’

Yet another excerpt recalls, ‘From the first floor balcony of the theatre, one could see music composer S.D.Burman’s home in the distance, a white bungalow with red trimmings called The Jet. It was located on what is now Linking Road, opposite where the Khar Telephone Exchange stands today. It is hard to believe that there was nothing between New Talkies and the Jet to obscure the view at that time. The fact that the Linking came into existence only after I was born just goes to show how old I am! How the tables have turned! SoBo has become moribund, and all the young millennials from there come to party through the night in our uber-cool and trendy suburb. Bandra was always known as the Queen of the Suburbs. If one considers the Bandra of my childhood as Queen Victoria, then the Bandra of today has got to be none other than Freddy Mercury.’

Joy, going back in time to your work in films. You assisted Shyam Benegal back in the 1980s. Do inform of your apprenticeship.

I joined filmmaker Shyam Benegal as his assistant in 1982 and my first film was Mandi. The whole experience was like a roller coaster ride. Never having worked before, I had no experience in this regard. I learned on the job and the hard way. I was the junior most assistant and I was bullied mercilessly all through. But Shyam got wind of it and took special care of me. I can never forget his kindness.

On the surface everything was superficially simple, but behind the scenes it was like Star Wars. Unabashed lobbying for favours, too many top actors, all bidding for more footage on screen at the cost of someone else losing out. I was a mute spectator, but I got a ringside view of the battles.

Then there were Trikal set in Goa and Susman, which took me back to Andhra again. This time I was the senior most assistant and I made sure I wasn't bullying my juniors. I also did some short films with Shyam. All I can say is that my stint with Shyam definitely taught me the ABC of filmmaking, but I have never used my knowledge to direct a film because I never felt I had a burning message for mankind. My father made meaningful films, dealing with controversial and burning social issues like untouchability and the plight of farmers. It was a hard act to follow, so I took the easy way out. I quit before I had even started!

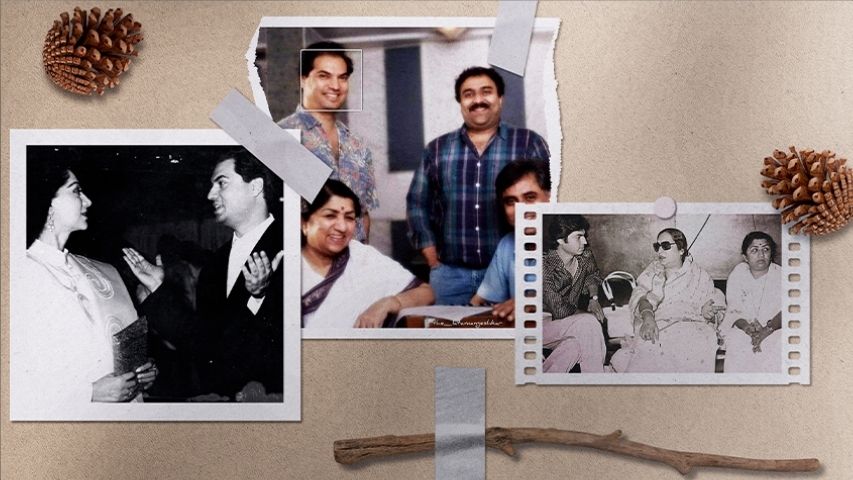

You had a long tenure at Saregama (formerly known as The Gramophone Company of India Ltd). Do share your work experience.

Sometime in 1989 my late brother-in-law Pradeep Sinha introduced me to a friend who headed the music company Saregama. A few months later Pradeep called and said his friend had offered me a job. I wasn't remotely interested in a corporate job so I consulted my Guru. I knew he would save me. But to my horror he promptly said: Take the job. I usually followed everything he said so I started on one Saturday morning in March 1990. I stayed for 5 years.

It was an exciting job. I was Artiste and Repertoire Manager, which meant I had to look after the singers, composers, film producers and create music with them. Though I knew Lata Mangeshkar from much before I joined HMV, it was here that I got to know her better and even shot two music videos with her.

One of my favourites was Jagjit Singh. He was such a charmer. It was an enriching experience despite the fact that my boss disliked me and did everything possible to thwart me in whatever I did. But that only increased my determination. Ultimately his dislike became so toxic that I decided to quit the job. But the memories of the good times have always stayed with me.

One learns from the websites that after Bimal Roy’s death the family retained his office at Mohan Studio in Andheri till they were told to vacate the premises by a builder. That's when in 1999 Joy Bimal Roy visited the studio. On the first floor was Bimal Roy’s editing room and library where he kept stock shots and live sounds. In the editing room Joy discovered half-a-dozen reels tagged 'Kumbh Mela'. Bimal Roy had started a film, 'Amrit Kumbh Ki Khoj Mein', based on Samaresh Basu's novel, 'Amrita Kumbher Sandhane'.

Now the son started watching the negative and discovered it was a one-hour footage of the 'Kumbh Mela' in Allahabad and the negative was in perfect condition. He edited and curated the footage as a documentary tribute to his father, but didn't have the funds till Yash Chopra approached the family for the overseas video rights of Bimal Roy's films. Joy told him about the Kumbh footage, which he could incorporate as a bonus. Yash Chopra allowed Joy the use of his editing facilities and his editor. Joy cut a 11-minute documentary, which begins early in the day and ends with an aarti on the Ganga at night.

Since it was silent footage, Joy had to decide on the sound. Sound engineer Arun Nambiar, came up with the idea of using music from his father's own films. Joy took his idea forward, using music from Devdas for the train shots and Madhumati for the mela sequences, a scene of a pandit speaking matched with a scene of another pandit speaking in Parakh. Kabuliwala's 'Ganga aaye kahan se' was used since Kumbh is all about the Ganga. The documentary premiered in January 2000. It is now on YouTube.

Now to go back to Bimal Roy’s beginnings. He was from Suapur, Dhaka. He came from Bangladesh (then East Pakistan) in the early 1930s to Calcutta with his father. He had to struggle. Even though from a zamindar family they saw oppression in the struggle. Bimal Roy’s first job was as a still photographer with P C Barua. Later in Barua’s New Theatres Bimal Roy became assistant cameraman. His first work as cinematographer was the K.L. Saigal starrer Devdas. What a beginning!

My father's move from Dhaka to Kolkata was the result of a tragedy, which probably scarred him for life. On the death of my grandfather the estate manager managed to transfer our ancestral property to his own name and threw out my father, two young brothers and my grandmother with just the clothes on. The first job that my father got was in a photo studio at a salary of Rs.15/- a month. He had to walk to work because he had no money for bus-fare. He was truly self-made. To rise from a photo-studio attendant to his stature is indeed a remarkable success story.

There is an incident from his New Theatres’ days that I want to share. Everyone was on a studio payroll in New Theatres, getting their salaries at the end of the month. No one was really wealthy. The custom was that whenever any employee got married one person would go around taking contributions from everyone, which was then handed over to the married couple. The amount was usually Rs 5. On one particular occasion two people were collecting money and one of them saw Baba leave and remarked to the other that Baba had left without paying his contribution. The other one said ‘Bimalda was one of the first to pay and he contributed Rs 500/-’ Baba was quietly generous.

Do inform of your mother Manobina Roy’s familial antecedents and of her contribution to your father’s work.

My mother Manobina hailed from an East Bengal family who had moved to Banaras three generations before her birth. My maternal grandfather was the Principal of Meston High School in Ramnagar, an all-boys school belonging to the Maharaja of Banaras. He was also a private tutor to the prince.

My maternal grandfather was a very progressive man. He treated his twin daughters, Manobina (my mother) and Debalina (my aunt), on equal terms as anyone else, man or woman, with the result they grew up to be remarkably independent-minded women. He brought home a private tutor from Kolkata for the girls because there was no school for girls in Ramnagar. And he bought them a Brownie camera when they were 12 and put up a dark room as well so they learnt how to develop. Little wonder that they grew up to be two of the earliest known women photographers of India. It is such a privilege to have such illustrious parents.

Bengal Famine (1943), English, was one of your father’s first works. Then came the feature film Udayer Pathey (Bengali) in 1944. He showed his stamp as a maker with social consciousness.

I have not seen Bengal Famine, but Udayer Pathey certainly made waves in Bengal when it was released. It could be considered as one of the most significant and important films of Bengal Cinema. The genesis of the film is worth sharing. In those days technicians and even actors were on the monthly payroll of New Theatres, including my father. It was his dream to make a film and finally he found a book by a new author Jyotirmoy Roy, which seemed just the right choice. In essence it is about the exploitation of the poor by the rich.

When he broached the topic to the head of the studio Shri B.N. Sircar, who was essentially a kind man but primarily a businessman, agreed conditionally. He said my father could make the film, but he would have to make it from the remaining pieces of film. This meant my father could only take short shots. He took up the challenge even further by taking a cast of all first timers. The film created box office history by running for a year and has the unique distinction of having its dialogues sold in the form of booklets from every pan shop in Kolkata. People actually recited its dialogue. My father became a cult hero overnight. It was a fantastic way to begin his new career as a director.

I am sharing an incident of these times. Baba had set his heart on buying a BMW car and it cost Rs 5000. It was back then a lot of money. The car was to be handed over in the studio. Baba brought the money in an envelope in his coat pocket. He took off his coat and went off to shoot. When he came back the envelope was missing. He mentioned it to his assistant who told me the story. Once again Baba didn’t turn a hair. The assistant said ‘Aren’t you going to ask everyone?’ Baba said, ‘What is the point? I am not going to get back the money’. End of story.

In 1951 he came to Bombay at the invitation of Devika Rani to join Bombay Talkies. Ma was the name of the first film here. He then settled in Bombay and carved an irreplaceable space in Hindi cinema. How did he develop a sense of Hindi language? He had a great ear for it.

I am told that if one excels even in one language then one can be proficient in another, because one can understand quality and nuances. My theory is that Baba had a great command over his mother tongue, Bengali, so when he heard the dialogue in Hindi he would translate it into Bengali in his head. Thereby he would automatically know if the dialogue conveyed what he wanted or it would need to be rewritten. But I am sure that over time his knowledge of Hindi grew by leaps and bounds and he no longer needed to translate. He was a voracious reader, which made him a literary man. Such men can always tell the difference between good and bad use of language.

After shifting his base to Bombay, by 1952 Bimal Roy had restarted the second phase of his career with Maa (1952), for Bombay Talkies. His team included Hrishikesh Mukherjee (editor), Nabendu Ghosh (screenwriter), Asit Sen (assistant director), Kamal Bose (cinematographer) and Salil Choudhury (music director). Look at the students who came out of the Bimal Roy School! Later Gulzar. Ritwik Ghatak, of course, as a story-writer of Madhumati. Tell us of your assessment of him as a teacher-boss.

In his interview for my film, Remembering Bimal Roy, on my father, Gulzar said that Bimal Roy Productions was like a film school and Baba was the Principal. My father nurtured talent and helped it grow.

Assistant cameraman Chuni Shah said Baba used to organize private screening of films for his team. After the film he would ask them questions about the film. There was a scene in a Russian film in which the camera follows the protagonist climbing several floors of a spiral staircase in one single shot. He asked the camera crew to explain how the shot had been taken. So, he made sure that his team was forced to think out of the box. He also helped actors grow by giving them leeway to interpret a scene in their own way.

Comedian Jagdeep, who was a child artiste in Do Bigha Zamin, said that he asked Baba if he could sing a few lines in his shot and then demonstrated what he had in mind. Baba was most enthused and told him to go ahead. He was able to get the best out of people by encouraging them and giving them confidence. He was nothing short of a Guru and therefore his company was like a gurukul where he created a guru-shishya parampara.

Bimal Roy educated his cine-literacy so exceptionally well. It is said that he was very fond of Russian films. He must have inculcated the taste in his children too.

Baba used to show us films on a 16mm projector at home too. I think it was his way of inculcating cine-literacy in us. He had a penchant for Russian films and I remember seeing a very depressing one called 'The Cranes are Flying'. But he also introduced us to the magical world of Chaplin, one of Baba's favourites.

Later I discovered there were two other directors he admired: Billy Wilder and William Wyler. Wilder is one of my favourites too. Baba didn't approve of us going to theatres, but a few weeks before he passed away he sent my two sisters and me to see Lawrence of Arabia. I am not sure why he did, because it was a very oppressive film, but to this day, the film is inextricably linked with Baba's death. In retrospect I wish he hadn't sent us to see this film because Lawrence's death became a metaphor for Baba's death.

In the year of your birth, 1955, Devdas got released. Till 1966 you had your father with you. Tragically you lost him at a very tender age. Do share some personal memories of him that rest in you.

Alas, I have very few personal memories of my father. He was such a dedicated filmmaker and a compulsive workaholic that he was hardly ever home. He would leave for work before I woke up and return after I was asleep. He took no days off. Gulzar joked that behind Baba's back the team would refer to him as a married print.

But there are two trips with him that stand out in my memory because I actually got a chance to spend some time with him. One was to Ooty in 1963. The other to Lebanon, Jordan and Greece in 1964. There are two special memories of these trips. I was a solitary child with few friends and my two companions were music and books. Unbeknownst to me Baba must have heard me sing some time and taken note of it. On our Ooty trip Baba heard S.D. Burman was in Coonoor, close to Ooty, so we went to visit him. I still remember being taken aback when Baba asked me to sing 'Mora Gora Ang Laile' for Sachin Jetha. And in Beirut he woke me up from my sleep to sing for the Indian Ambassador. After Baba died in 1966 I lost my singing voice and I can't sing a note now. After all these years I realize what a deadly impact Baba's death had on me. It was almost like I got a new persona. From an easy going gregarious and confident kid I became a shy introvert with hardly any friends. It is only after 60 that I came into my own once more. But I don't think I am going to sing again!

Were your father’s films the presence you later found of a patriarch in life? Was it also learning about him through his films? From Udayer Pathey (1944) to Do Bigha Zamin (1953), to Bandini (1963) to Life and Message of Swami Vivekananda (1964). I trust the last work was in 1964?

Actually, my mother played the part of both mother and father in my life so initially I didn't consciously miss a patriarch in my life. What changed all that were the interviews I did for Remembering Bimal Roy, the film I made on my father in 2007. I met people who had worked with him. They all spoke of him with such love and respect that I was moved to tears. For the first time I realised what I had missed and yet paradoxically I found him through those interviews. Making the film was one of the most cathartic and life-changing experiences. It was almost as though I found the father I had lost when I was just 11. I realized anew what a privilege and honour it was to be the son of such a man. Not only because he was such a great filmmaker, but because he was a great human being.

Do take us on a journey of his films as you have watched over the years. Your favorites among a tall order of films and how do you assess these. Also, of any valuable incidents related to the shooting of the films.

The first film I saw was Do Bigha Zamin and it was a traumatic experience. It was just after my father passed away. A film society had organized a screening in my father's memory and Ma took me along. It was in Chitra cinema in Dadar. Till today I can't bear to watch the end of the film. Ma used to tell us that she contributed to the end of Do Bigha Zamin. In the original story Nirupa Roy dies in the end. It was Ma who insisted that there should be at least some relief. Shambho could lose his property, but not his wife. Baba listened to her. And the rest is history.

Baba hadn't allowed us to see any of his films while he was alive so I perforce saw them after his death. My two favourite films are Madhumati and Sujata. Madhumati because it is one of the best scripts I have ever seen. It is amazing that one can watch the film again and again despite knowing the end. It grips you from the word go and doesn't let go of you till the end. And I love Sujata because of its purity. There is something so noble and chaste in the love that Nutan and Sunil Dutt have for each other. The film is deceptively simple. It is actually a layered plot, shunning prejudices with a very deft, subtle and sometimes tongue and cheek manner. And yet it is one of the most moving films I have ever seen. There is never a dry eye in the audience at the end of the film. True love truly conquers all.

It is difficult to be objective about his films, but I would say his Devdas is the one most true to the original. Dilip Kumar's portrayal as the tortured young Devdas has got to be one of the very best of his career. And I love Parakh too, a film far ahead of its time. I am told Baba was the first man in India to use a freeze shot. I could go on endlessly about his films.

I must also share with you some incidents that are marked. Baba was known to be a perfectionist so he usually took very few shots in the day. On one particular day while shooting with Dilip Kumar (either for Madhumati or Yahudi) he was unusually quick and took several shots. At the end of the day it was discovered that the assistant cameraman had forgotten to take the shutter off the camera. So, nothing had been exposed. Baba did not bat an eyelid. Dilip Kumar exploded and told Baba that the man should be sacked immediately. Baba quietly said, ‘We will reshoot tomorrow.’

Then in Sujata there is a music sequence, which shows Nutan at one with nature. Leaves sway in the breeze. In the last shot Baba wanted to show a leaf twirl and then Sujata would twirl like the leaf. Baba and the unit waited patiently all day for the leaf to twirl. According to Gulzar, Baba exposed at least 10,000 feet of film for a 10 second shot. Finally, the cameraman Kamal Bose got tired of waiting and told Baba, ‘Bimalda, why don’t you use a fan?’ Baba looked at him pityfully and said quietly ‘Kamal, you haven’t learnt anything yet.’

Bimal Roy alternated between music directors Salil Chowdhury and S.D. Burman. Lyricists were Shailendra, Sahir Ludhianvi. His films featured beautiful and memorable songs, rendered by all the top playback singers of the day. Songs were scenes. Parineeta had music by Manna Dey/Arun Mukherjee and lyrics by Bharat Vyas. Which are your favourite songs from his repertoire? And do inform us of his musical ear.

It is hard to choose just one or two favourite songs because music was one of Baba's fortes. Every film had outstanding music. I think he got the best out of everyone he worked with. I also surmise that he worked very closely with both lyricist and composer because his songs were not stand-alone, they were part of the plot and story. So, it was extremely important for the melody and lyrics to fit into the story. It gave a positive synergy to the team to come up with the best results. And they did, time and again.

But just for the record I do have some personal favourites: ‘Dil tadap tadap…’ (Madhumati), ‘Kali ghata chhaye…’ (Sujata), ‘Yeh mera deewanapan hai…’ (Yahudi) and ‘O sajana….’ (Parakh) to name just a few.

Your mother (one of the first women-photographers in Bengal) was such a collaborative presence. In a video interview she says that her husband would discuss his script situations with her. Perhaps he wanted a woman’s opinion.

I think Ma was the perfect ardhangini for my father. They were like two halves who made a perfect whole. They complemented and supported each other completely. It was undemonstrative but it was clear their union was one of mutual respect.

Do share with us as to who were the filmmakers, Indian and foreign, who influenced or shaped Bimal Roy’s aesthetics?

I have already mentioned Billy Wilder and William Wyler earlier. Let me add Frank Capra to the list. I don't think I heard about his preferences for Indian filmmakers. There was also a Chinese American cinematographer he admired. James Wong Howe.

Your father was of the Nehruvian times. It is said that Nehru would grace the special screenings arranged by your father. Any anecdotes?

I have heard that Nehru liked Baba's films. In fact he asked my father to organize a private screening of Sujata because he had heard so much about it and the story goes that he wept at the end of the film. Am enclosing the letter he wrote to Baba after the screening.

In a video interview your mother says that Bimal Roy in the end was very worried about his studio and staff. The last conversation she had with him she assured him that she will take over. Next day he was dead.

Yes, indeed Ma gave her word she would look after the staff after Baba's death and she kept her word. It was a Herculean task because Ma had no money, as Baba had died without making a will. But our lawyer collected the dues on our behalf and helped Ma to make payments. She was indeed a remarkable person. She made the transition from housewife to producer in one fell swoop. One more feather in her cap!

Do you look forward to more remakes of your father’s works by others?

I don't look forward to remakes if they are the kind SLB (Sanjay Leela Bansali) made out of Devdas. I think classics should not be tampered with. There are enough new subjects you could choose from. Why choose to re-make something that has already been made and seen before? It doesn't make cinematic sense to me.

Bimal Roy received a whole line-up of awards at the national and international level. Filmfare award itself is aplenty. There are his precious original scripts and films. Joy’s house is a veritable heritage of our collective cine-history. Bimal Roy is among us - far more present today than even yesterday.

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)

-173X130.jpg)